Ultrametricity and additivity criteria for phylogenetic trees: Why do they matter?

In the Fall of 2016, I was a graduate TA for an introductory course on computational genomics. One of the rewards of teaching the class was re-learning some of the material such that I can explain it in an intuitive and clear fashion to the confused students (this is called the Protége Effect). One of my most memorable example of this phenomenon was the confusion amongst students about the ultrametricity and additivity criterion for phylognetic trees. Most students were capable of understanding and regurgitating the mathematics behind these criteria and how they can be applied to building a tree, but most failed at explaining its importance. Here is how I presented it to my students. This may not be a completely accurate explanation but it was the clearest explanation that students could digest iniitally

A phylogenetic tree is simply a representation of the history of how species evolved from a common ancestor. In phylogenetic analysis, evolution is approximated by differences in genome sequences, which is, in the most crude sense, a function of mutations occurring over time within species that diverged from a common ancestor. If the distance matrix of a group of species is ultrametric, it allows you to make the following assumption about these species: the evolutionary rates (e.g. rate of mutations over time) have been constant, which consequently allows you to use UPGMA to build a tree.

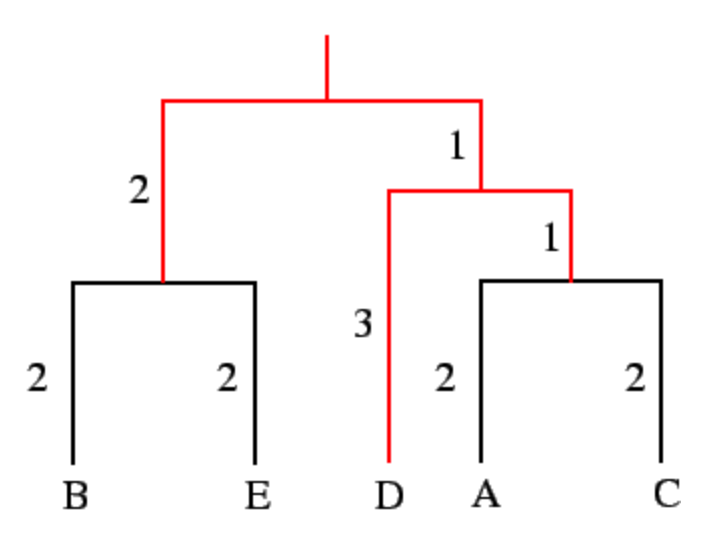

But what does that really mean? What is it about the ultrametricity criterion, $$ M_{ij} = M_{jk} \geqslant M_{ik}, $$ that is important for tree building?! How does the assumption of constant mutation rate simplify tree building?! Let me illustrate by an example. See the attached for a tree (that I got from here).

Let us focus on the leaves \(D\), \(A\), and \(C\). The distance are as follows

- \(d(A,C)=2+2=4\),

- \(d(D,A)=3+1+2=6\),

- \(d(D,C)=3+1+2=6\).

In this case, \(d(D,A)=d(D,C)=6\) but either of those distances is larger than \(d(A,C)=4\). So, we can apply the following:

- Because the distances between \(A\) and \(C\) are smaller than distances of each to \(D\), we can cluster \(A\) and \(C\) together.

- Because the distance of \(A\) and \(C\) to their closest relative \(D\) are equal, we can assume that \(A\), \(C\), and \(D\) share a common ancestor.

So, to recap, the inequality (smaller than) criteria allows you to cluster species into artificial nodes where they have been assumed to diverge in their history, while the equality allows you to relate them in a equidistant fashion to their second closest relative.

The additivity criteria is just a bit more complicated than the ultrametricity criteria. So, I won’t try to illustrate it here, as I did above for ultrametricity. But you can apply a similar logic to understand intuitively why the additivity criteria, $$ (M_{ij} + M_{kl}) = (M_{il}+M_{jk}) \geqslant (M_{ik}+M_{jl}) $$ is important for building a phylogenetic tree. Nonetheless, I would like to emphasize how additivity is different from ultrametricity. In reality, mutations occur at different rates during speciation events. So, two species that are related to a common ancestor might not necessarily be equidistant from their common ancestor. In such a case, a phylogenetic tree that is additive allows you to relax the erroneous (but simplifying) assumption that the rates of mutation leading to species events is constant.